To the premium subscribers, thank you for your support - it allows me to write these deep-dive briefings and continue to provide the weekly newsletter for free.

To the free subscribers, this is a short preview. If you would like to read more, please upgrade your subscription. You should continue to receive the free weekly newsletter as usual.

Preamble

Biodiversity is no longer just a concern for conservationists and activists, but a fundamental aspect of climate goals, food security, risk disclosures, and increasingly even corporate strategy. Yet while we recognize the need to protect nature, several reports from organizations and initiatives such as IPBES, UNEP, CBD and TNFD* have pointed out, we still struggle to measure it in a consistent, scalable way.

This is where Earth observation (EO) comes in. While satellites can’t see species or genes directly, they offer a way to get continuous insights into the ecosystems, habitats, and pressures that shape biodiversity. As frameworks like GBF and TNFD push for better monitoring, EO is quickly becoming an essential layer in biodiversity intelligence.

In this deep dive, I unpack the role of EO in biodiversity monitoring: where it adds value, how it integrates with other data, the market landscape, and what it will take to build a truly global biodiversity monitoring system.

Note: While often used interchangeably, it’s worth noting that biodiversity refers specifically to the variety of life - from genes and species to ecosystems. Nature, on the other hand, includes biodiversity but also encompasses landscapes, natural processes, and the broader environmental systems they are part of. This piece focuses exclusively on biodiversity monitoring, not the wider concept of nature (related – see previous deep dives on carbon markets and wildfire monitoring).

*Acronyms used above and throughout the piece

- IPBES - The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services is an independent intergovernmental body assessing the state of biodiversity and ecosystem services.

- UNEP - United Nations Environment Programme is the UN agency that coordinates environmental activities and assists countries in implementing environmental policies.

- CBD - The Convention on Biological Diversity is a multilateral treaty aimed at conserving biological diversity, promoting sustainable use, and ensuring fair benefit-sharing from genetic resources.

- TNFD - The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures is a market-led initiative developing a risk management and disclosure framework for organizations to report and act on nature-related risks.

- GBF - The Global Biodiversity Framework, formally known as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, sets global targets to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030.

Here is what we have in store for this briefing:

- Context: What is Biodiversity?

- The State of Global Biodiversity

- EO for Biodiversity Monitoring: Overview

- Role of Remote Sensing

- Essential Biodiversity Variables

- EO for Biodiversity Monitoring: Market Segmentation

- From Observing to Managing

- Operationalising EO-based Biodiversity Solutions

- Outlook: Towards a Global Biodiversity Monitoring Systems

Context: What is Biodiversity?

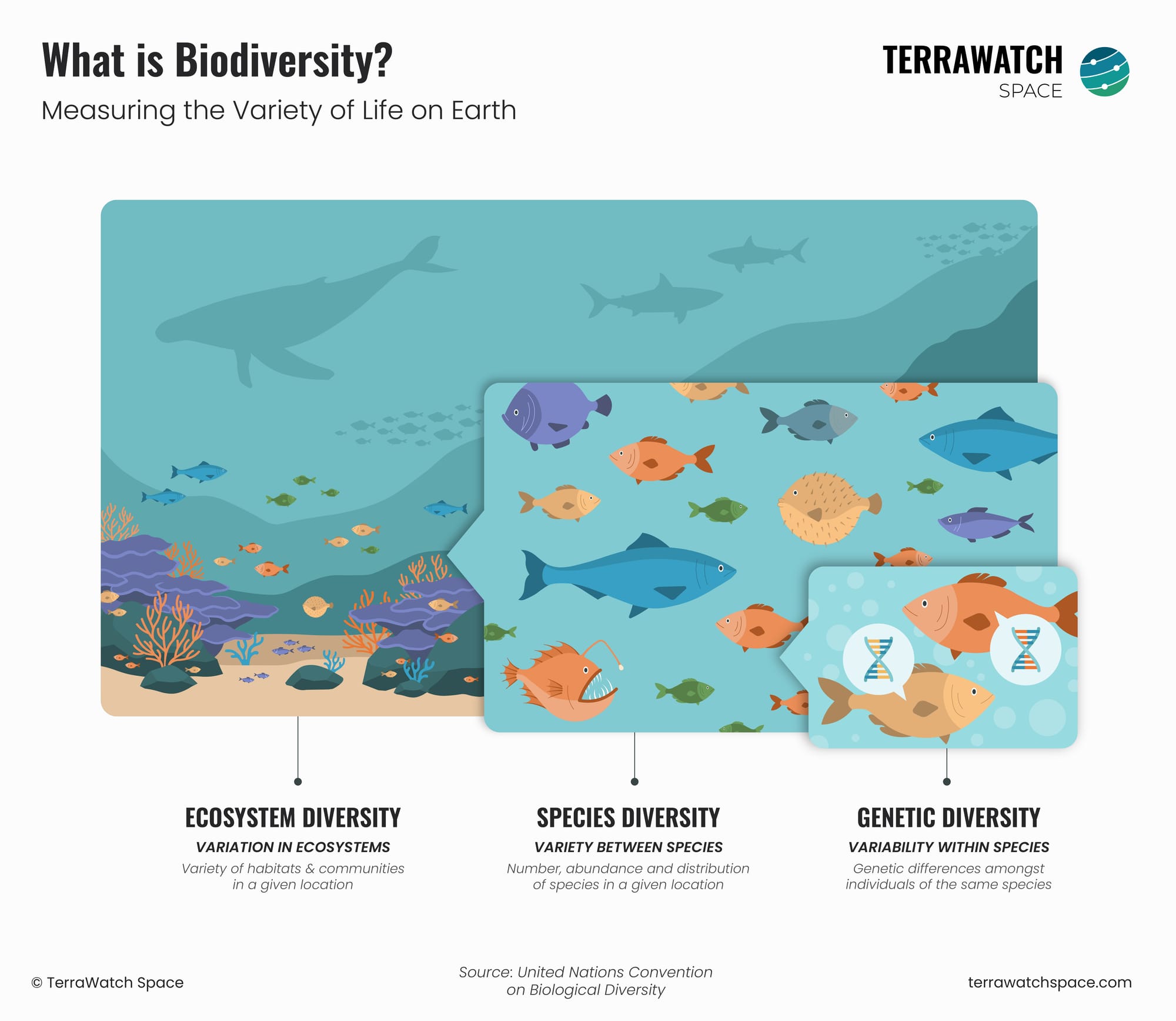

Biodiversity refers to the variety of life on Earth, spanning three levels: genetic diversity, species diversity and ecosystem diversity.

- Genetic diversity: The variation of genes within a species, which enables populations to adapt to changing environments and resist diseases.

- Species diversity: The variety of living organisms within an ecosystem, from microscopic plankton to large mammals.

- Ecosystem diversity: The broad range of ecosystems and habitats across the planet including forests, wetlands, coral reefs, tundra, and more.

Biodiversity supports the functioning of natural systems - everything from enabling water purification and climate regulation to supporting soil formation and crop pollination. In addition, it is also deeply linked to cultural values and spiritual identity in many communities.

Yet biodiversity is often invisible in public discourse. Unlike climate change, which is increasingly quantified easily quantifiable (temperatures in °C and carbon dioxide levels in ppm), biodiversity loss is harder to distill into a single number. Biodiversity loss happens more silently and unevenly with local extinctions, ecosystem collapse, or genetic erosion that may go unnoticed until it’s too late.

In the UK, ash trees are dying silently due to a fungal disease, with over 90% expected to vanish in some regions. More than 900 species rely on ash, and by the time the scale of loss became clear, it was too late to stop. What began as a quiet decline now threatens ecosystems and even public safety, as dead trees line roads and paths.

The State of Global Biodiversity

The science is clear: biodiversity is in crisis.

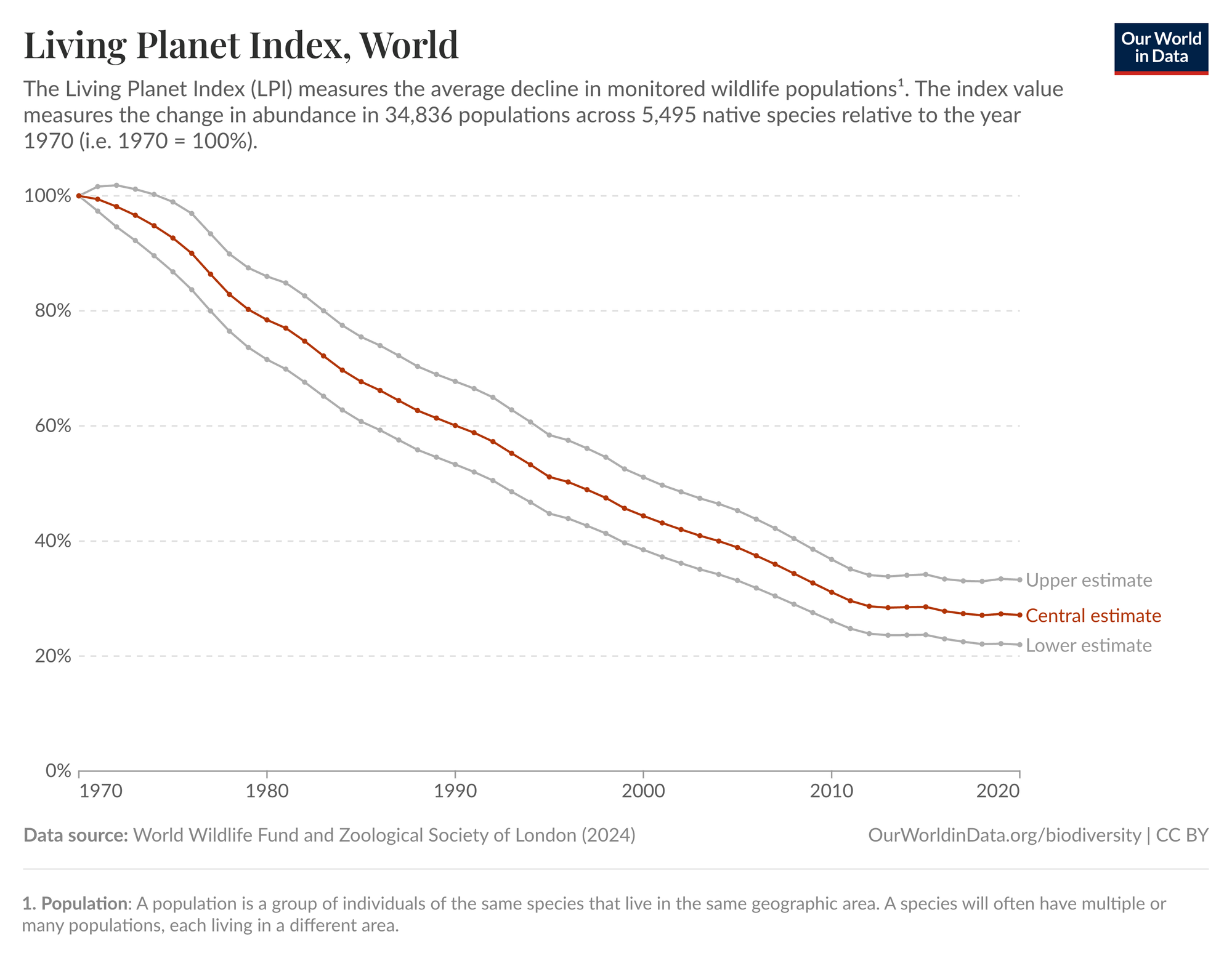

According to the IPBES Global Assessment, around 1 million species are at risk of extinction. In addition, IPBES reports that 75% of terrestrial environments and 66% of marine environments have been significantly altered by human activity. The WWF Living Planet Index shows a 69% average decline in vertebrate populations since 1970.

The figure below shows the figures from the recent Living Planet Index, which tracks changes in global vertebrate populations relative to 1970 levels. As of 2024, monitored populations had declined by 73% on average.

This decline, according to the report, is mainly driven by five factors:

- Land and sea-use change such as deforestation, agricultural expansion, and coastal development.

- Direct exploitation of organisms including overfishing, hunting, and illegal wildlife trade.

- Climate change altering habitats, species ranges, and ecosystem dynamics.

- Pollution from pesticides, plastics, heavy metals, and nutrient runoff.

- Invasive alien species non-native plants, animals, or microbes that disrupt local ecosystems. Behind these are systemic drivers: economic incentives, governance gaps, lack of data, and short-term decision-making

What makes biodiversity loss unique and, some argue, even more dangerous than climate change is its irreversibility. Once species go extinct or ecosystems collapse, they cannot be easily regenerated. And without biodiversity, some of our climate solutions like carbon storage in forests or wetlands will start to fail. This is why the GBF calls for urgent action to halt and reverse nature loss by 2030.

To protect biodiversity, we must first be able to observe and monitor it. That’s where EO comes in.