This is the longest and most complex deep dive published on TerraWatch. It is designed to give an in-depth look at the weather enterprise, from value chains and AI models to use cases and public-private roles. We have done our best to simplify (not oversimplify) weather for everyone.

Much of it is free to read because weather is foundational, but the full piece is reserved for Premium subscribers or available as a standalone report to buy.

Lastly, this is a follow-up to the (free) deep-dive that was published in 2022. Please consider reading that one for a more comprehensive understanding, though this piece also stands on its own.

Context

Everyone checks the weather. It decides what we wear, how we travel, whether crops get planted, or if planes take off on time. From crops to cargo ships to credit markets, forecasts save billions of dollars and help generate billions of dollars. Weather is the one thing we all complain about, but behind the small talk it is silently running the global economy.

Growing up in a tropical country - India - I have had my fair share of extreme weather experiences. Irrespective of where you are and where you grew up, we all have a weather story to share, both as an individual and as a business. But, weather has probably never mattered more than it does today.

As we are constantly reminded, we are living through a time when not only the weather is changing but how we predict the weather is also being reshaped. Dozens of new weather satellites and hundreds of weather balloons are being launched every year, generating unprecedented volumes of atmospheric data. AI models are now producing forecasts in minutes, not hours, and thanks to strong marketing, every new model promises to be the best, most accurate model that has ever existed.

Modern weather forecasting traces back to a single storm: the Royal Charter disaster of 1859, which spurred Robert FitzRoy to issue the first storm warnings. Just as that storm reshaped weather in the 19th century, AI now promises to reshape forecasting as we know it.

The story of weather today is no longer just about whether it rains tomorrow. If you think weather is just about knowing when to carry an umbrella, you are probably missing the bigger story. Weather has become so strategic that even Microsoft, Google, and NVIDIA are moving in.

But even as the market seems like it is shifting, the foundations remain the same: governments still operate the backbone of the system – satellites, models, forecasts, and early warnings – while private companies are increasingly pushing the frontier with new sensors, models, and tailored services. Weather is no longer just background information, it is becoming critical infrastructure that is built on a public backbone, extended and improved by private players.

With that context, here's what we will cover in this deep dive:

- The Weather Value Chain

- How observations, models, products, and insights fit together

- Weather from Space

- The role of satellites + distribution of public & private weather satellites

- Traditional vs AI Weather Models

- A visual explainer of the two approaches, and how they compare

- The Commercial Landscape

- Key players, business models, and market evolution

- Weather Use Cases

- Who buys weather intelligence, and how demand is shifting across sectors

- Public vs Private

- The evolving roles of each, but why both need to coexist

- Forward Look

- The platformization of weather

- Conclusion

The Weather Value Chain

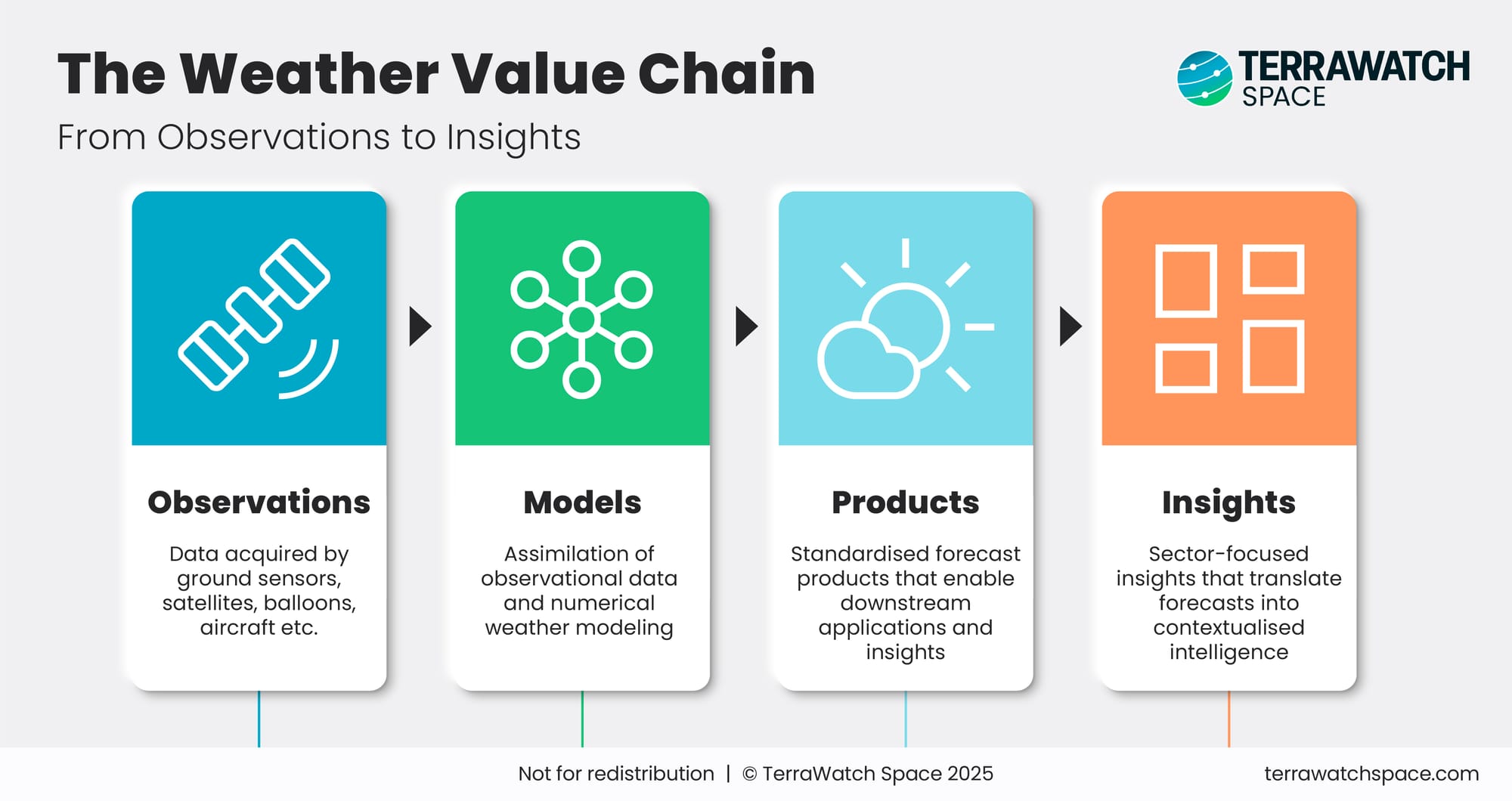

At its core, the weather enterprise runs on a chain of dependencies. Every forecast you see – from a government warning to the app on your phone – is the end result of four tightly linked steps.

- Observations form the foundation. Satellites, radars, balloons, aircraft, and ground stations feed raw data about the atmosphere, oceans, and land into the system. Without this, nothing else works.

- Space-based observing systems constitute approximately 90 percent of the data used in global numerical weather prediction models (more below)

- Models take those observations and, through data assimilation and physics-based equations, generate a picture of the current state of the atmosphere and simulate how it might evolve.

- Weather models are run on some of the world’s fastest supercomputers, using thousands of CPU cores and updated every ~6 hours (more below)

- Products turn those model outputs into usable formats: forecasts of temperature, precipitation, wind, and more, typically delivered via APIs or SaaS platforms or mobile apps.

- Weather APIs now handle billions of requests daily, powering everything from aviation systems to enterprise workflows.

- Insights translate those forecasts into decisions. This is where raw data becomes sector-specific intelligence - crop yield predictions for farmers, risk scores for insurers, or outage probabilities for utilities.

- Insights ensure that actual value is created by embedding forecasts into user workflows and decision systems.

As you see, each layer depends on the one before it, but the value grows as you move rightward. Data is abundant. Intelligence is scarce. The big question in the weather enterprise today is not about who can observe or who has the models, but who can turn those into trusted, actionable insights.

Weather from Space

Weather satellites are the backbone of global forecasting. Data from the UK Met Office showed that the share of contribution of weather satellites for a 24-hour forecast grew from 73% in 2019 to 77% in 2024. Globally, the contribution of data from satellites stands at about 90%. In other words, while ground-based observational infrastructure remain vital, without spaceborne data, modern weather forecasting would collapse.

Weather Satellites: Stats & Figures

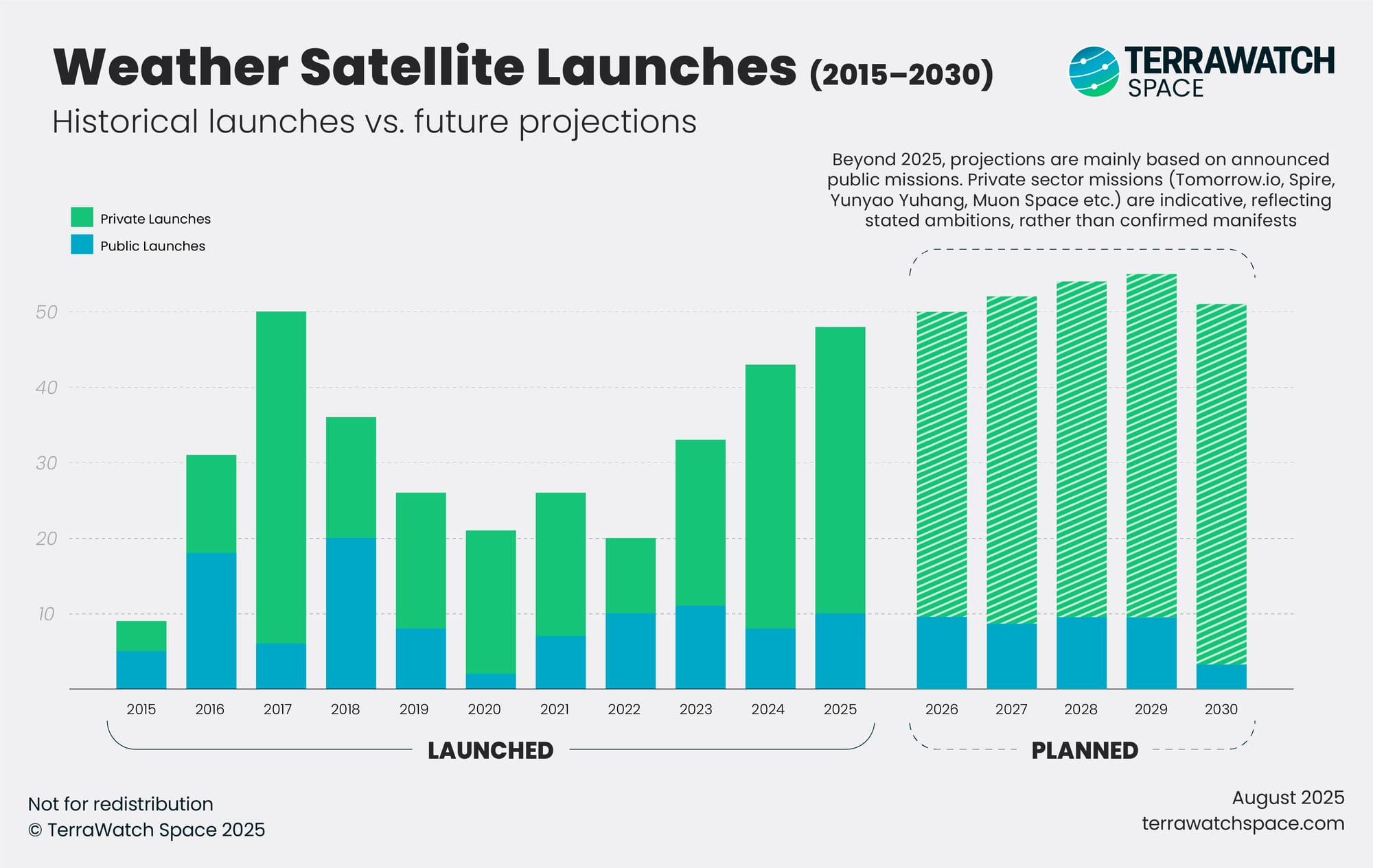

The visual below shows that between 2015 and 2025, the number of weather satellites launched has steadily grown, with private launches increasingly matching or exceeding public ones in some years. Beyond 2025, the picture becomes less clear: most firm launch manifests are still public, while private numbers reflect stated ambitions rather than confirmed deployments.

This divergence underscores the dynamic we see today: public agencies remain the foundational providers of weather data, but private firms are scaling rapidly and pushing into domains once thought out of reach.

Weather Instruments: Quick Overview

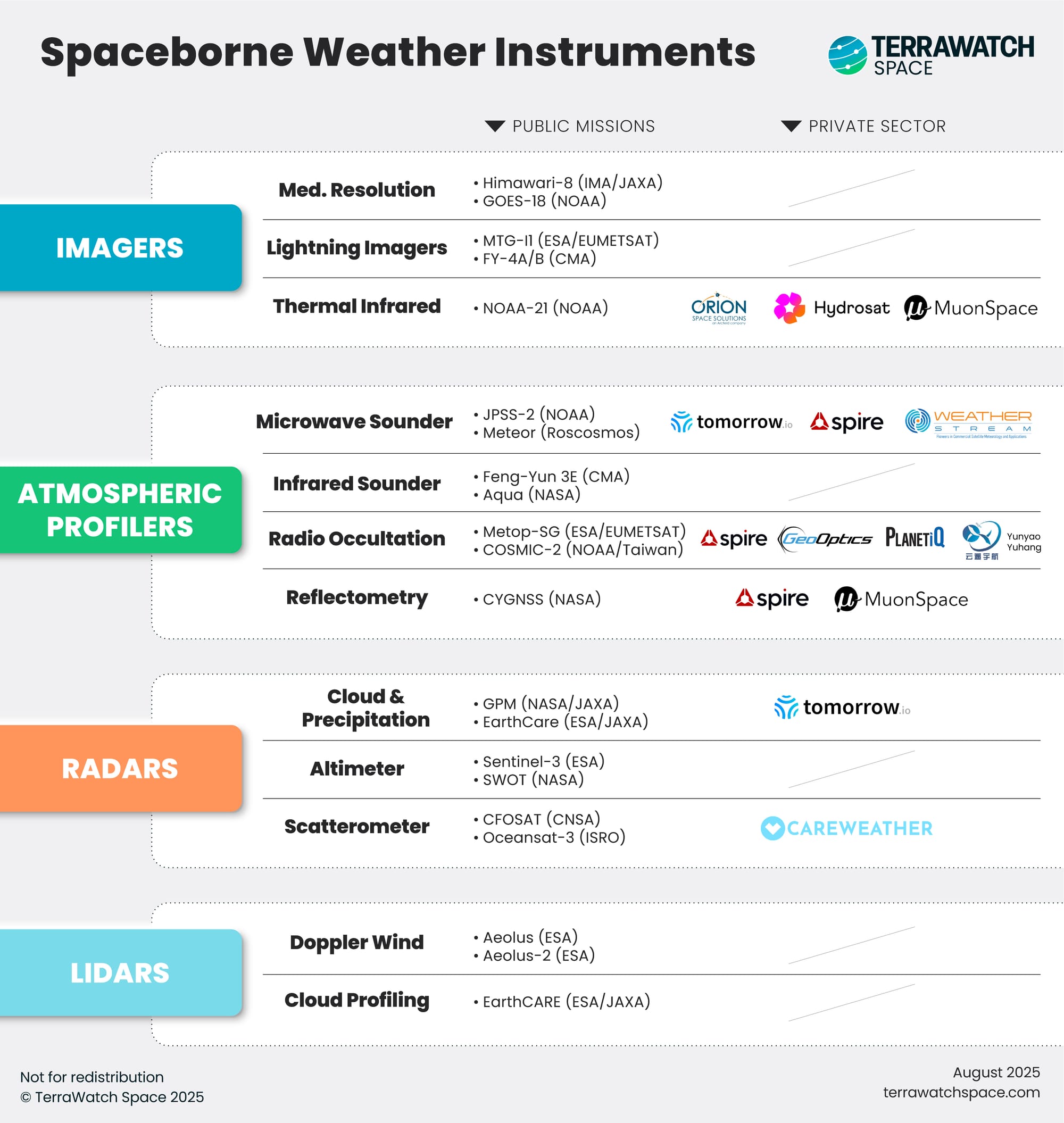

What exactly are all these satellites carrying? The chart below breaks that down. Spaceborne weather satellites host a wide range of sensors, each probing different parts of the atmosphere.

- Imagers for cloud, lightning and surface monitoring,

- Atmospheric profilers including microwave sounders, radio occultation, and reflectometry provide vertical structure of temperature, pressure, and humidity,

- Radars for precipitation and winds,

- Lidars for wind and aerosol profiling.

Historically, these capabilities were almost entirely developed and operated by public agencies such as NOAA, EUMETSAT, JMA, CMA, and others. But in the last decade, private players have started to build and deploy their own constellations: Spire, Tomorrow.io, MyRadar, and others are now fielding GNSS-RO and microwave sounders, complementing data from the public sector.

Of course, satellites only tell us what the atmosphere looks like right now. To know what happens next, you need models and that’s where the story gets interesting.

Traditional vs AI Weather Models

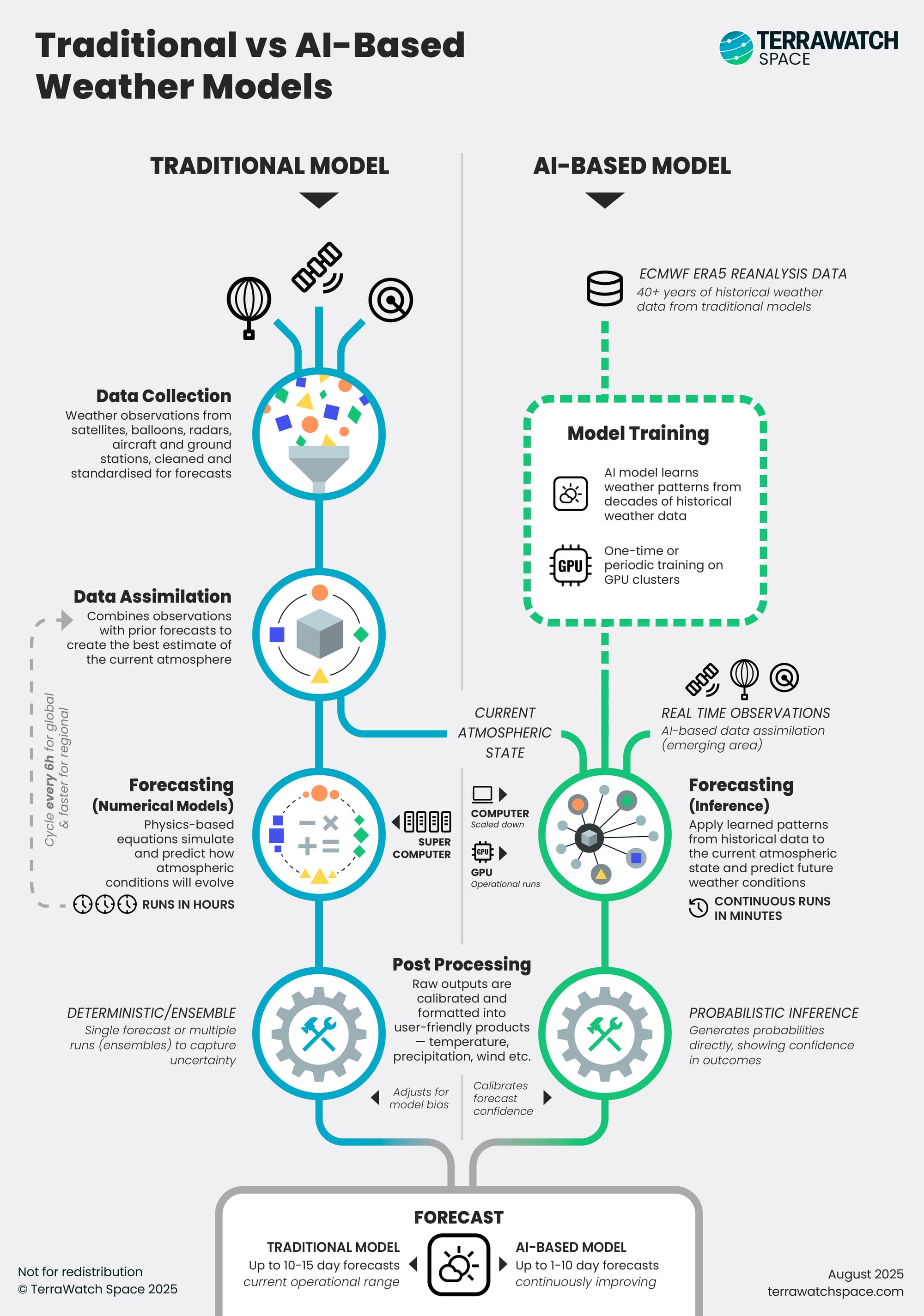

For decades, weather forecasts have been generated almost exclusively through Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) – massive physics-based equations processing the atmospheric data, running on some of the world’s fastest supercomputers. Now, a new wave of AI-driven models is challenging that paradigm, offering forecasts in minutes on GPUs or even laptops.

The shift is not about replacing one with the other, but understanding how these two approaches compare and where they may converge.

Buy the standalone State of Weather 2025 report for US$99!

To read the full piece, please upgrade to the Premium tier, or buy the standalone report.