Disclaimer: This article is not a professional write-up or a sponsored blog, but rather the ramblings of an Earth observation evangelist who is passionate about making satellite data more accessible and easy to use to help us better understand our planet and make efficient data-driven business decisions.

Recap

In my first post, I explored the analogy of the Video Streaming sector and the Earth Observation (EO) sector focusing on the similarities in search costs involved for customers in finding content in streaming providers and finding data in EO data providers. In my second post, I wrote about the significance of evangelizing EO and how it is critical for its long-term growth, more so than for its short-term revenues. In my third post, I experimented with organising the EO industry based on a software operating stack and explored if there can ever be a Google for EO. In this post, I would like to muse over my carefully crafted but unproven guide to building a unicorn company in the Earth observation sector.

Unicorns …

In the tech world, a unicorn is a fancy word given to a company whose valuation is over $1 billion, cheekily named after the mythical animal to represent the uniqueness of such hugely successful companies. However, since the word was coined in 2013, almost 500 companies (as of Nov. 2020) have joined the “unicorn club”, with the fundamentals of the taxonomy already under question (maybe werewolves, since we probably get one unicorn every 28 days?!). This list mainly comprises of companies in various industries such as e-commerce, travel, fintech and so forth. The unicorn club currently includes two big names in the space industry — SpaceX and Rocket Lab — but could soon be joined by others including Momentus and Virgin Orbit. Some reports claim that OneWeb and Kymeta are also on the road to becoming unicorns, as well as Planet Labs and Spire Global from the Earth observation sector.

… and Earth Observation

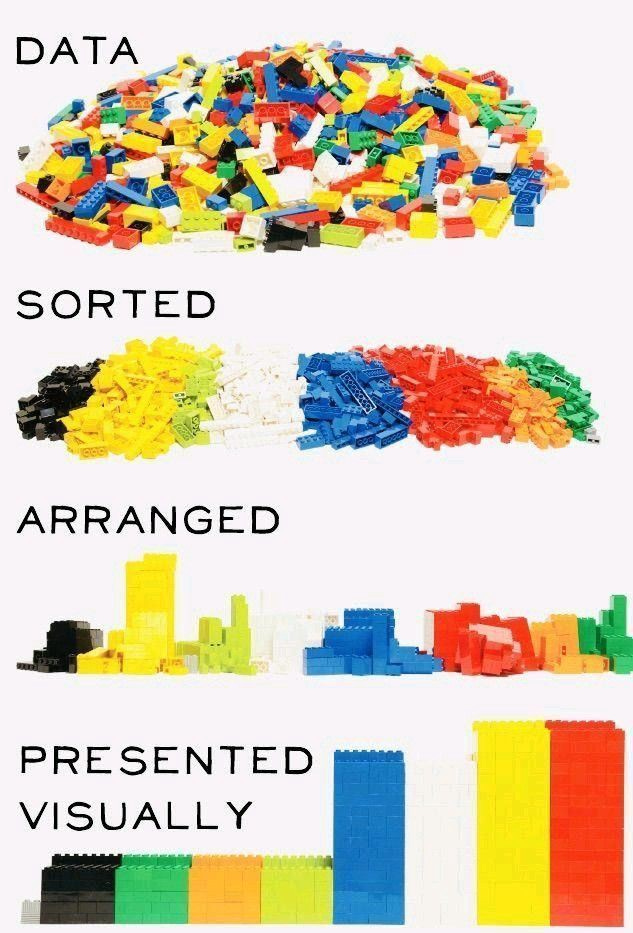

As I have written in my pieces before, the Earth observation market is incredibly fragmented. For the sake of simplicity, I usually classify the Earth observation sector into three layers (Data, Platform and Insights), now supported by this extremely handy “infographic.”

Data: The Data Layer (the one concerned with the generation and collection of EO data through satellites),

Sorted: The Platform Layer (the one concerned with the storage and distribution of EO data and some derived analytics), and,

Arrange and Presented Visually: The Insights Layer (the one concerned with the applications built from EO data).

With a potential total market size for Earth observation ranging from $5 billion to $50 billion, can we actually find unicorns in EO? Will they be the companies building and launching satellites in the Data Layer? Or, will they be from the increasing number of marketplaces and data platforms in the Platform Layer? Or, perhaps they might be in the Insights Layer, among companies that actually try to make sense of this cool data from space?

You might ask, why care about unicorns at all, or you might have strong opinions about whether this phenomenon of unicorns should exist at all. You are right. I personally would rather build camel companies, those that can resiliently survive for longer periods and can adapt to variations. But unfortunately, unicorns do make the news. And EO needs as much publicity as it can get, to become the multi-billion-dollar market. So, I am going to go ahead with this premise, anyway. Bear with me!

Before we delve into the guide, a few quick definitions:

- Vertical: A market in a particular industry/sector/domain (e.g. agriculture, retail, insurance, banking, climate tech, mining and so on)

- Data-as-a-Service: A subscription-based model to acquire EO data

- Software-as-a-Service: A subscription-based model to acquire software products derived from EO data.

Building Unicorn Companies in Earth Observation

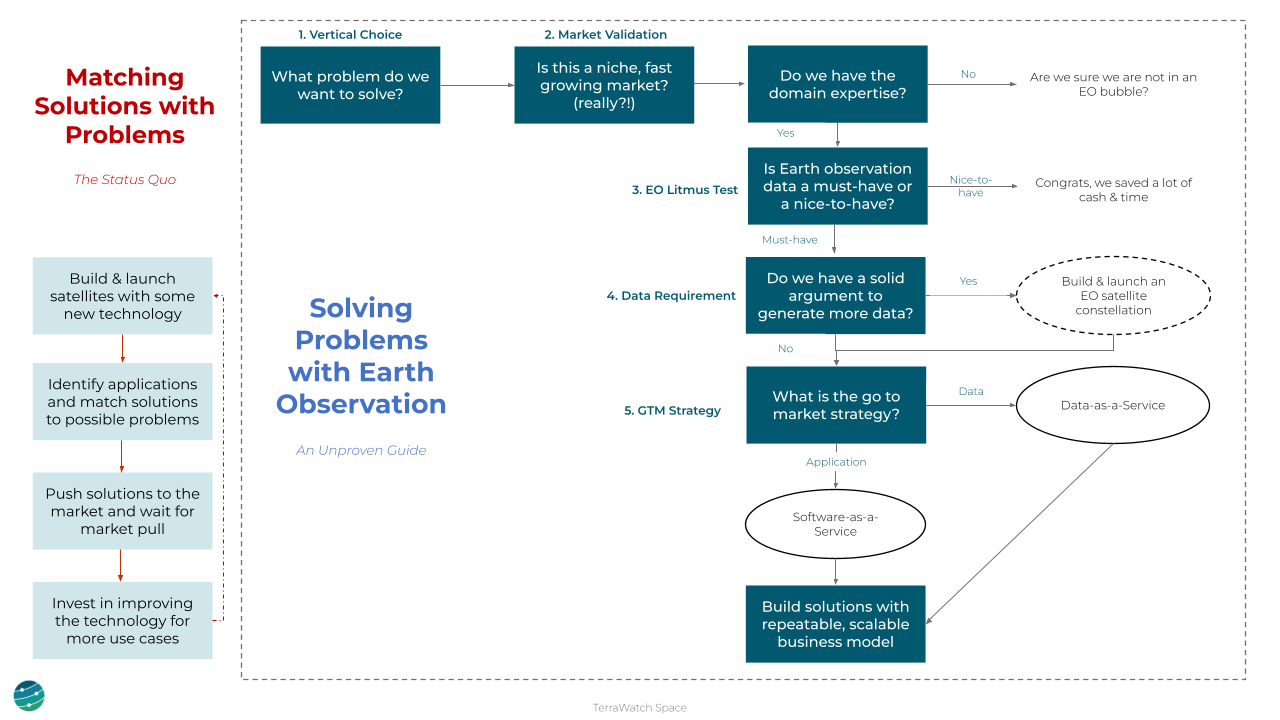

Matching Solutions with Problems — The Status Quo

We launch satellites with truly incredible sensors fully aware that the data that they collect has applications across the board. Meaning, we have a technology that has countless solutions for various kinds of problems, and that’s a great thing. Unfortunately for EO, we are trying to solve too many problems at the same time. So, once we launch, we start matching solutions to potential problems. Then, we wait for the technology we created to find its magical billion-dollar market, instead of actually going and competing for our share of the pie.

From collecting data using sensors that might make some sense to a naked eye (optical panchromatic, video, etc.) to those that make absolutely no sense (multispectral, SAR, hyperspectral etc.), I have been fascinated with all things EO ever since I switched careers from the software industry into the wonderfully weird world of space and Earth observation. But, why is it that this incredibly valuable technology has not become common across industries? Why haven’t we able to generate any unicorns or even remotely successful companies yet even though the applications of EO data spread across domains? Will there be any big success stories in the short-term from the EO sector that will set the precedent?

In my humble opinion, I believe the answer lies in the cliched question, “what is the problem we are trying to solve?” With that in mind, I propose this carefully crafted, free, unproven guide for building the next unicorn in the Earth observation sector.

Solving Problems with Earth Observation — An Unproven Guide

Step 1: Vertical Choice: What problem do we want to solve?

This is the most important step. Simply put, what problem do I want to try and solve with Earth observation? Meaning, this is already where we choose the vertical(s) to target, not after launching satellites. I am a big fan of the “Jobs-to-be-Done” framework. People usually buy a product to “get a job done.” So, in order for our technological innovation to be adopted by customers, we should rely less on ‘what we are trying to sell’, ‘what technology it uses’ and rather focus on ‘what is the underlying task that this product does’. In other words, the first step needs to be ‘what specific problem is the product solving, using EO data?’ rather than ‘EO data is great for solving lots of problems.’ This first step probably needs to be focused on one specific problem in a vertical, or potentially adjacent verticals. This guarantees that there is a depth-first analysis of the vertical and of the corresponding market dynamics, which is important for the following steps. This vastly differs from the usual breadth-first analysis across industries to gather potential applications of EO data that takes place today.

Step 2.1: Market Validation: Is this a niche, fast-growing market?

Going in-depth into a vertical and asking if the product, powered by satellite data, can actually “get the job done” for a customer, helps one understand the trends in that specific vertical market. Is the market we are targeting actually niche and fast-growing? Do we have the opportunity to become the “stars”, as referenced on the BCG matrix? More often than not, we might find that EO data is great for building lots of applications in various sectors, but some of them might be in markets where there is just not enough addressable market. If there is not enough market because of the lack of adoption of EO data, it is perhaps solvable through evangelising and education, but this can only be done for products that are actually getting a job done for customers, in which case customers might actually pause and listen to this new technology from space. Sure, there might be products worth building simply because it is just possible to build them, but it is essential to be fully aware that they might end up being pets and question marks.

Step 2.2: Market Validation: Do we have the domain expertise?

This might sound controversial, but we are living in a bubble, an EO bubble. Most of us are remarkable scientists, spacecraft engineers, remote sensing specialists and geospatial experts, but the majority of us are not domain experts. I am a generalist, one who shamelessly tries to be a jack of multiple trades and a master of none, so I don’t count myself into any category here. But, the vast majority in the EO community are very knowledgeable and experts in some sub-domains of EO, but very few fully understand the vertical markets of the satellite data applications they target. I have found that those who do possess some expertise in particular verticals end up being more from the scientific side than from the commercial side. Sure, one might go ahead and hire a professional or a practitioner in specific verticals with decades of experience, after the satellites are launched and data is available, in order to go sell it to the customers in the verticals. But they might be still stuck with the same challenge — trying to find problems for the solutions. Maybe one can find a balance by co-developing the product along with an anchor customer in a specific vertical. But, in any case, I believe it is probably better to possess the domain expertise (or have the means to acquire it) in the vertical(s) of choice well ahead of time —before the bubble bursts.

Step 3: EO Litmus Test: Is EO data a must-have or a nice-to-have?

This might sound controversial, again, but EO data is not as useful as we think it is. For some problems, EO data is a nice-to-have, and for others, it is a must-have. The idea is to then focus on the must-have category if one wants to build an EO-based company. It is also perfectly all right to build companies with EO data as a nice-to-have. In fact, those companies have all the chances of becoming unicorns simply by avoiding the time and money saved from having to deal with satellite imagery. But doing this litmus test, with domain expertise gathered in the previous step, becomes even more crucial. Some verticals might have been using satellite imagery for decades (oil & gas, weather, agriculture) more so than others (financial services, climate tech, insurance). Doing this exercise can also help identify the positioning in the market (for step 5). As a result of this, unfortunately, we might find out that there are some substitutes (aerial, drone, IoT, location data) that “get the job done” better than EO data, in which case, one could choose to just fuse all data, and call ourselves a deep-tech company instead of an EO (or space) company.

Step 4: Do we have a solid argument for generating more data?

If I were to put on my consultant hat, the first recommendation I would give for anyone wanting to start up an EO company is, “not to build satellites, even if it is absolutely necessary.” As naive as it sounds, this is both for the sake of the space environment (space debris!) and for their business case. Obviously, there are exceptions to this rule and there might be solid arguments for launching new EO satellites such as the price of data, new technological innovation, geopolitical needs or simply because “they found investors.” This is because I think the task of demonstrating new technology, building and launching satellites is so much easier than the task of helping to make sense of the data. So, my preferable exception to the aforementioned rule is, “build satellites as long as the new data generated is going to help the jobs to be done.” This is why I am guessing companies with exciting technological advancements in SAR, edge computing, hyperspectral, radio frequency, infrared etc. are getting new VC investments. Or at least I am hoping it is the case and that they will get that job done.

Step 5: Strategy: What is the go-to-market strategy?

This step is important for positioning the company on the Earth observation operating stack (from my last piece). Depending on whether the company focuses on data or application, the go-to-market strategy (GTM) might differ.

- Data-as-a-Service: If the target customer profile knows and understands remote sensing, this might be the best GTM strategy. However, it might not be easy if the sensor being launched is SAR or hyperspectral, in which case, specific enabling tools might be needed in order to guarantee success (unless of course, the customer is just defence in which case, selling data contracts might work as the defence sector is quite sophisticated).

- Software-as-a-Service: This is more likely to happen given the company will have a solid understanding of the problem, possess the required domain expertise and knows the customer needs. In fact, I expect companies already with a software product to go through this exercise and add another data source their proprietary technology, which can help differentiate with similar companies operating in the same vertical.

Having gone through all these steps, I reckon the biggest challenge is still the last one. Building solutions by cracking the repeatable, scalable business model which is basically the significant component of the unicorn puzzle — unit economics. In my last article, I explored the concept of an application layer in the operating stack of Earth observation and whether there can ever be a Google for EO. After much reflection, I think it might be a lost cause. I don’t think there will be one Google application for EO, but there will probably be multiple application stacks in EO, depending on the problem and vertical of choice.

There can be an operating stack for emission monitoring, an operating stack for carbon monitoring, and operating stack for maritime surveillance and so on. I have come to realise that only by focusing on a particular set of problems in specific verticals can we unlock the scalable, repeatable business model, simply because buying habits, pricing activities and selling capabilities are very unique to a vertical. We might probably need to stop looking for generic one-size-fits-all solutions and instead go with a specific, vertical based approach, leading to vertical based EO operating stacks.

Scalable, repeatable business models might after all not be possible with the status quo — focus on multiple problems to solve with little collaboration among those in the EO ecosystem, which is made worse by a limited understanding of the customers’ jobs-to-be-done.

PS. What about horizontal EO companies?

Although I have focused a lot on vertical-based solutions, I have always wondered about the position of the horizontal players — the marketplaces, and the platforms in the EO ecosystem, and whether they can become stars or unicorns or just simply successful. For starters, I think they do a ridiculously, brilliant job of organising complex EO data, making processing algorithms easily available and getting the complex pricing models of data providers to be more digestible for end users.

But, going back to my unproven guide, I believe the answer lies, once again, in the first step, “what problem do we want to solve?” Making satellite data accessible and democratised is a very fair value proposition, solving a clear job-to-be-done. However, for horizontal players, an additional, “for whom?” might be pertinent given different customers in different verticals might want to access satellite data differently. So, perhaps there might be vertical marketplaces and domain-specific platforms (like the Thematic Exploitation Platforms of ESA), and therefore, they will have a role to play within the vertical-specific operating stacks? I admit I don’t have the answer quite figured out yet. This is still an unproven guide!

Until next time,

Aravind.